March 31, 1980

The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 is signed into law by President Jimmy Carter.

The statute:

- Increases the deposit insurance limit from $40,000 to $100,000.

- Restores the assessment credit to 60 percent and links it to the reserve ratio.

- Provides for the gradual removal of deposit interest-rate ceilings originally mandated during the Great Depression, in response to disintermediation caused by both the ceilings and a sharp rise in interest rates. Ceilings are to be removed by 1986 (this occurred in March 1986).

- Allows all depository institutions to provide checking account services and Negotiable Order of Withdrawal (NOW) accounts or their equivalent.

- Grants thrift institutions expanded powers that before had been available only to commercial banks.

- Establishes phased-in uniform reserve requirements for depository institutions.

- Requires the Federal Reserve to provide services, including access to the Discount Window, to all depository institutions for set fees.

For a discussion of the statute, see FDIC, History of the Eighties: Lessons for the Future, (1997): 91-93, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/87_136.pdf .

For the increase in deposit insurance coverage to $100,000, see Christine M. Bradley, “A Historical Perspective on Deposit Insurance Coverage,” FDIC Banking Review 13 no.2 (2000): 17-20, https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/archived-research/banking-review/br2000v13n2.pdf .

For the change in the assessment credit, see Lee K. Davison and Ashley M. Carreon, “Toward a Long-Term Strategy for Deposit Insurance Fund Management,” FDIC Quarterly 4 no. 4 (2010): 31, https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/fdic-quarterly/2010-vol4-4/fdic-quarterly-v4n4-fundmgmt-121610.pdf .

For more detail on the monetary control provisions, see Kenneth J. Robinson, “Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980,” Federal Reserve History, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/monetary-control-act-of-1980 .

April 28, 1980

First Pennsylvania Bank, N.A. receives open-bank assistance. At the time, First Penn, with $8 billion in total assets, was the 23rd largest bank in the United States, and its failure would have been the largest in U.S. history. (It should be noted that the FDIC generally considers a bank that received open-bank assistance to have failed.) The bank had purchased large quantities of longer-term fixed-rate government securities in the late 1970s, but interest rates had continued to rise quickly and deposit rates greatly exceeded the rates earned on those securities. In addition, the bank had a large number of nonperforming or underperforming loans, amounting to more than the bank's total equity capital. Since no acceptable merger partner was available, and a payoff of the bank's depositors would have led to a sizeable depletion of the FDIC's fund, federal bank regulators assembled an open-bank assistance package that included loans from the FDIC and other banks and a line of credit from the Federal Reserve.

See FDIC, Managing the Crisis, 515-526, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/documents/history-consolidated.pdf .

December 31, 1980

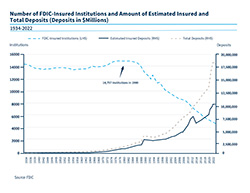

There are approximately 14,750 FDIC-insured institutions with estimated insured deposits of about $950 billion.

1980

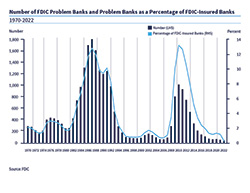

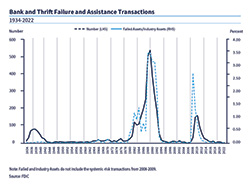

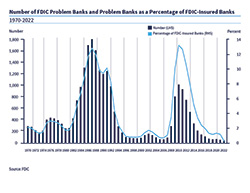

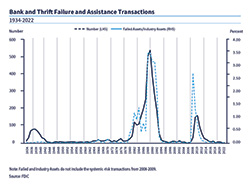

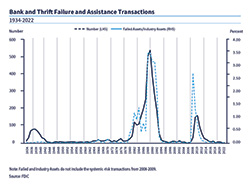

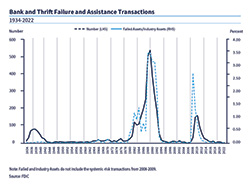

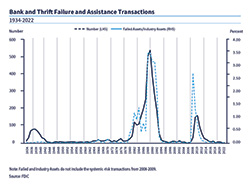

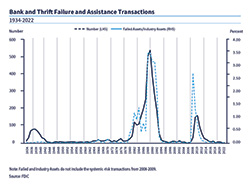

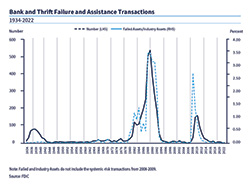

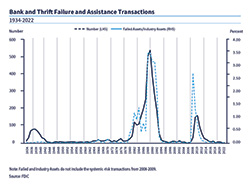

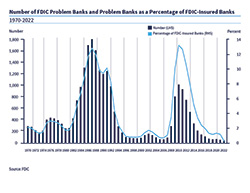

Eleven FDIC-insured banks and 11 FSLIC-insured thrifts fail in 1980. There are 217 FDIC problem banks.

August 3, 1981

William M. Isaac becomes the 13th Chairman of the FDIC and serves until October 21, 1985. Isaac, a native of Ohio, was appointed to a six-year term on the FDIC's Board of Directors in March 1988. From 1974 to 1988, he was vice president, general counsel, and secretary of First Kentucky National Corp. and its subsidiaries. From 1969 to 1974, he practiced law in Wisconsin.

1981

Ten FDIC-insured banks and 34 FSLIC-insured thrifts fail in 1981. There are 223 FDIC problem banks.

July 5, 1982

Penn Square Bank, N.A. fails. Penn Square, an Oklahoma City Bank with $516 million in assets, had grown more than eightfold in size in just five years by making aggressively large and speculative loans in the energy sector, which began to experience difficulties the year before the bank's failure. Penn Square sold loan participations to 53 banks, including $1 billion of participations to Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Co., which would receive open-bank assistance in 1984. The FDIC decided that the least cost to the FDIC's fund entailed a payoff of Penn Square's insured depositors. Only about $208 million of the bank's about $470 million deposits were insured, making Penn Square at the time the largest failure in FDIC history in which uninsured depositors suffered losses.

See FDIC, Managing the Crisis, 527-542, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/documents/history-consolidated.pdf .

October 15, 1982

The Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 is signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

Largely a deregulatory attempt to rescue the thrift industry, this law:

- Allows federally chartered thrifts to offer demand deposits.

- Requires that any differentials on maximum allowable interest rates on deposit accounts between banks and thrifts be removed by 1984.

- Gives additional powers to federally chartered thrifts.

- Mandates the creation of money market deposit accounts (that could compete with money market mutual funds).

Important to the FDIC, the law also enhances its powers to provide aid to troubled institutions.

- Regulators could make a loan to a failing institution, make a deposit in such an institution, purchase its assets, purchase securities it had issued, and assume its liabilities.

- The law expands the FDIC's open-bank assistance authority. The essentiality test is eliminated except when the cost of open assistance would exceed the cost of liquidating the institution.

- The statute also provides, for three years, for the purchase of net worth certificates from troubled institutions; these certificates would be counted as capital and so could allow a troubled institution to continue operating until it returned to health.

- The law also enhances the FDIC's ability to find acquirers for failing institutions by permitting the agency to authorize emergency interstate acquisitions of certain closed banks and interstate mergers or takeovers of certain mutual savings banks in danger of failing.

See FDIC, History of the Eighties: Lessons for the Future, (1997): 84-95, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/87_136.pdf .

For the FDIC's net worth certificate program, see FDIC, History of the Eighties: Lessons for the Future,” (1997): 227-230, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/211_234.pdf .

December 7, 1982

The FDIC announces the provisions of its Net Worth Certificate (NWC) Program. Under this program, designed to address ongoing problems at mutual savings banks, the FDIC increased or maintained a participating institution’s regulatory capital. Basically a type of capital forbearance, the NWCs were to remain outstanding until the institution became profitable. Twenty-nine savings banks would participate in the program.

See FDIC, History of the Eighties: Lessons for the Future, (1997): 227-30, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/211_234.pdf .

1982

Forty-two FDIC-insured banks and 73 FSLIC-insured thrifts fail in 1982. The number of FDIC problem banks rises to 369.

July 1983

In a TV report from July 1983, Jane Bryant Quinn on CBS Morning News reviews 50 years of FDIC history. This video also includes speeches from then-Chairman William Isaac and then-Vice President George Bush

November 30, 1983

The International Lending Supervision Act of 1983 is signed into law by President Ronald Reagan. As a result of the less-developed country (LDC) debt crisis and its potential effects on U.S. banks, Congress moves to ensure sound banking practices. The law is primarily aimed at large banks with significant lending exposure to LDCs. Among its provisions, the law requires each bank regulatory agency to ensure that all banking institutions maintain adequate capital levels.

See FDIC, History of the Eighties: Lessons for the Future, (1997): 113, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/87_136.pdf .

1983

48 FDIC-insured banks and 51 FSLIC-insured thrifts fail in 1983. The number of FDIC problem banks rises to 642.

May 17, 1984

Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust, then the seventh-largest bank in the United States, receives open-bank assistance. Continental had been aggressively growing since the late 1970s and became the largest commercial and industrial lender in the nation. Continental had also made significant loans to less-developed countries (LDC loans). The bank had little retail business and relatively few core deposits, relying on fed funds and brokered deposits. After Penn Square's failure in 1982 (Continental had purchased $1 billion in loan participations from Penn Square), the bank was forced to use foreign money markets at higher rates. The LDC debt crisis contributed to a sharp increase in the bank's nonperforming loans, and Continental's financial situation became increasing precarious. Large foreign depositors feared the bank would fail and in May 1984 began a high-speed electronic run on the bank. Concerned that a crisis might envelop the entire banking system, federal bank regulators crafted an assistance package for Continental. This package includes a capital infusion from the FDIC and some commercial banks, as well as the Federal Reserve meeting any liquidity needs and major U.S. banks providing further unsecured funding while a permanent solution was sought. The FDIC publicly guaranteed that all depositors and other general creditors would suffer no loss. With the FDIC unable to find a merger partner, Continental was permanently resolved by, among other things, the FDIC purchasing billions of dollars in bad loans from the bank and infusing $1 billion of capital into Continental by acquiring $1 billion in preferred stock in the bank's holding company, effectively making Continental a government-owned bank. The bank was required to replace its management. It would take until 1991 for the FDIC to sell all of its stock and complete Continental's return to private ownership. Continental's failure would cost the FDIC $1.1 billion.

See FDIC, History of the Eighties: Lessons for the Future, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/235_258.pdf .

See FDIC, Managing the Crisis, 527-542, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/documents/history-consolidated.pdf .

1984

Eighty FDIC-insured banks and 26 FSLIC-insured thrifts fail in 1984. The number of FDIC problem banks rises to 848.

March 1985

The Ohio Deposit Guarantee Fund (ODGF) is declared insolvent. Established in 1956, the ODGF, a private insurance cooperative, insures 71 state-chartered thrifts in Ohio in 1985. Following news of losses and the insolvency of Home State Savings Bank, depositors run on ODGF member thrifts. Continued deposit outflows lead Ohio’s Governor to declare a bank holiday, closing all ODGF insured thrifts. A law is enacted requiring the closed thrifts to obtain federal deposit insurance, and only those thrifts deemed likely to get either FDIC or FSLIC insurance were allowed to fully reopen. In May, the state legislature enacted a law that would cover ODGF losses, and eventually all ODGF insured depositors recovered their deposits.

May 1985

TThe Maryland Savings Share Insurance Corporation (MSSIC) is declared insolvent. Established in 1962 to insure deposits in state-chartered thrifts in Maryland, MSSIC-insured thrifts, following the events in Ohio in March, experience a “silent run.” In April it is announced that MSSIC-insured thrifts had lost $375 million in deposits since March. In May a criminal investigation is launched into Merritt Commercial Savings and Loan, and rumors circulate about financial problems at Old Court Savings and Loan. On May 14, the Maryland Governor imposes a withdrawal limit on MSSIC-insured institutions. Maryland would assume responsibility for all MSSIC-insured deposits, and all insured deposits were paid.

https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/chronological/1985.html

October 21, 1985

L. William Seidman (1921-2009) becomes the 14th Chairman of the FDIC and serves until October 17, 1991. Before becoming Chairman, Seidman had been Dean of the College of Business of Arizona State University and a director of several corporations. He served as Director of the White House Conference on Productivity, Vice-Chairman of the Phelps Dodge Corporation, Assistant to the President for Economic Affairs, and Managing Partner of Seidman and Seidman, Certified Public Accountants. He was also Chairman and Director of the Detroit Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Seidman received an AB from Dartmouth College, an LLB from Harvard Law School, and an MBA from the University of Michigan. Seidman's tenure occurred during extremely challenging times at the height of the banking and savings and loans crises. The FDIC handled more than 1,200 insured institution failures during his term, and the FDIC Board served as manager of the Resolution Trust Corporation charged with handling failed savings and loans.

1985

One hundred twenty FDIC-insured banks and 54 FSLIC-insured thrifts fail in 1985. The number of FDIC problem banks rises to 1,140.

August 10, 1987

The Competitive Equality Banking Act of 1987 is signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

The primary motivation for the law is to aid the deteriorating financial situation of the FSLIC, which was accomplished by creating the Financing Corporation (FICO) to serve as a financing mechanism to recapitalize the ailing insurance fund. The FICO is authorized to issue just over $10 billion in bonds.

Other important provisions include:

- Authorizing the FDIC to create “bridge banks” (temporary national banks) for up to three years to deal with failed banks when an immediate acquisition was not possible but when liquidating the bank was problematic.

- Making permanent and expanding the emergency interstate acquisition provisions adopted in 1982.

- Providing for a loan-loss amortization program for small agricultural banks.

- Stating for the first time, in statute, that insured deposits are backed by the full faith and credit of the United States. This statement had been articulated but never as part of a statute and therefore had never been made binding on the United States.

- Closing a statutory loophole that had permitted the chartering of so-called nonbank banks. (A 1970 law had defined banks as both accepting demand deposits and engaging in commercial lending, but if they did only one and not the other, banks escaped Federal Reserve regulation under the Bank Holding Company Act. Now banks were defined as any institution insured by the FDIC and any institution that both accepted transaction accounts and made commercial loans).

https://www.fdic.gov/about/financial-reports/reports/1996/legis.html

See FDIC, History of the Eighties: Lessons for the Future, (1997): 97-100, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/87_136.pdf .

On FICO, see https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/5500-600.html .

October 30, 1987

With the failure of Capital Bank and Trust Company in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the FDIC uses its new bridge bank authority for the first time. The FDIC determined that a bridge bank was in this case the most cost-effective way to preserve existing banking services and provide enough time to arrange a permanent resolution. The bridge bank was acquired in May 1988. The FDIC goes on to use its bridge bank authority to resolve a number of large and complex banks during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

1987

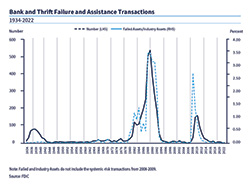

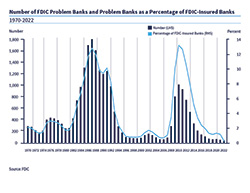

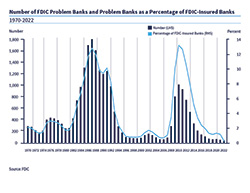

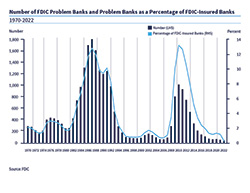

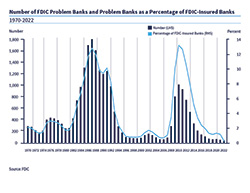

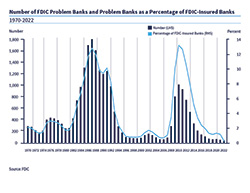

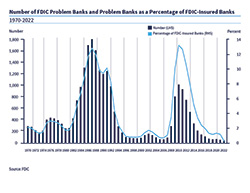

Two hundred three FDIC-insured banks and 48 FSLIC-insured thrifts fail in 1987. The number of FDIC problem banks during the banking crisis peaks at 1,575.

March 17, 1988

First RepublicBank Corp. of Texas, the 14th largest bank holding company in the United States with $33.4 billion in assets, receives open-bank assistance. This bank holding company (BHC) had been created by a merger only nine months before the assistance transaction. Although the merger was designed to assist one merger partner (InterFirst Corp.) that was suffering losses, it became apparent that the other partner (RepublicBank Corp.) was also troubled. Both banks were highly concentrated in real estate lending, and the new merged entity had a large net loss for 1987 due to deterioration in the Texas real estate market and reserving for losses on loans to less-developed countries. News of its extensive losses created funding problems for the BHC; its banks suffered significant depositor withdrawals, generating a liquidity crisis and putting First Republic on the verge of failure, which led First Republic to seek FDIC assistance. The FDIC put in place an assistance agreement that included a $1 billion loan, but First Republic’s banks continued to deteriorate and the FDIC considered potential assisted restructuring plans. On July 29, 1988, the OCC declared FirstRepublic-Bank Dallas insolvent and it was closed, which meant a default under the open-bank assistance terms. When the FDIC demanded repayment, it rendered the other First Republic banks insolvent, and they too were closed. The FDIC then approved an assisted acquisition of the First Republic banks by NCNB Corporation, a Charlotte, North Carolina-based BHC, from among the interested bidders.

See FDIC, Managing the Crisis, 595-615, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/documents/history-consolidated.pdf .

April 20, 1988

First City Bancorporation of Texas Inc. receives open-bank assistance. First City was an $11.2 billion Texas-based bank holding company with 59 Texas bank subsidiaries. Conditions at First City deteriorated due to downturns in the agricultural, energy, and real estate sectors. First City approached the FDIC for assistance in 1987, with a proposal from an outside investor group to inject new capital into the bank. After an extended period, the open-bank assistance transaction is approved. However, First City's problems would continue, and by 1990 the bank was again reporting a loss. The bank failed in 1992.

See FDIC, Managing the Crisis,” 567-593, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/documents/history-consolidated.pdf .

July 1988

The Basel I Capital Accord is approved and released to banks. A multinational agreement, it calls for a minimum ratio of capital to risk-weighted assets of 8 percent to be implemented by 1992. Most countries with active international banks adopted this framework.

https://www.bis.org/bcbs/history.htm#basel_i

1988

Two hundred seventy-nine FDIC-insured banks and 185 FSLIC-insured thrifts fail in 1988. The number of FDIC problem banks is 1,406.

March 28, 1989

MCorp, then the second largest banking entity in Texas and the 36th largest in the United States, fails. The FDIC elected not to provide MCorp with its sought-after open-bank assistance, and 20 of MCorp’s banks with $15.7 billion in assets were declared insolvent, though five of its subsidiary banks with $3.2 billion in assets remained open. The FDIC used its bridge bank authority to assist in the resolution. The bank had concentrated its lending in both the energy and real estate sectors, both of which were experiencing significant problems during the mid-to-late 1980s.

See FDIC, Managing the Crisis, 617-632, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/documents/history-consolidated.pdf .

August 9, 1989

The Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act (FIRREA) of 1989 is signed into law by President George H.W. Bush.

FIRREA is primarily meant to deal with the savings and loan (S&L) crisis.

The Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB) and the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC) are abolished. The FHLBB is replaced with a new federal savings institution regulator, the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), an agency under the Treasury Department and with the Federal Housing Finance Board, which takes over from the FHLBB in its role overseeing the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system. The law also creates the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC), a limited life government corporation tasked with resolving failed S&Ls. Initially, the FDIC serves as the RTC’s manager (the FDIC’s Board of Directors served as the RTC’s Board of Directors), and an Oversight Board is charged with setting RTC policy. FIRREA provides the RTC with initial funding of $50 billion—$18.8 billion from the U.S. Treasury, $1.2 billion from FHLB system member banks, and $30 billion raised through a bond issue through an entity called the Resolution Funding Corporation. This funding will prove insufficient.

The FSLIC's insurance fund is replaced with a new fund, the Savings Association Insurance Fund (SAIF), managed by the FDIC. The FDIC's fund is renamed the Bank Insurance Fund (BIF). The FDIC now is responsible for deposit insurance for both banks and savings institutions.

The makeup of the FDIC's Board of Directors is changed for the first time since the agency's creation: there are now five members, a Chairman, a Vice Chairman, an additional Board member, and the Comptroller of the Currency and the Director of the newly created OTS who are ex officio members. The Board cannot include more than three members of the same political party.

Importantly for the FDIC, the law provides that the FDIC can recover part of the costs of liquidating or assisting a troubled insured institution by assessing those costs against the solvent insured institutions in the same holding company. This is known as cross-guarantee authority.

For a summary of FIRREA, see FDIC, History of the Eighties: Lessons for the Future (1997): 100-102, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/87_136.pdf .

For the creation of the RTC, see Lee Davison, “Politics and Policy: The Creation of the Resolution Trust Corporation,” FDIC Banking Review 17, no. 2 (2005): 17ff,

https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/archived-research/banking-review/br17n2full.pdf .

1989

Two hundred seven FDIC-insured banks, 8 FSLIC-insured thrifts, and 318 thrifts for which the RTC was responsible fail in 1989. (The RTC in 1989 took over responsibility for insolvent thrifts that had been FSLIC-insured). The number of FDIC problem banks decreases to 1,109.