Creation of New York Clearinghouse

Before the clearinghouse existed, banks in New York settled their accounts by using porters to travel daily from bank to bank, exchanging checks for gold specie; eventually, the banks shifted to a weekly tally of accounts, every Friday. This was a cumbersome and error-prone process, made worse by the increasing number of banks in New York. After more than a year of discussion, most New York banks agreed to establish a clearinghouse to clear checks, thus settling balances. Clearinghouses in other cities would soon follow, including Boston in 1856, Philadelphia in 1858, Chicago in 1865, and St. Louis in 1868.

James Cannon, Clearinghouses and Credit Instruments, Publications of the National Monetary Commission Vol. VI (1911) https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/clearing-house-methods-practices-619 .

New York Clearing House Association Records 1853-2006. http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/archival/collections/ldpd_7094252/ .

Panic of 1857

Before the Panic of 1857, the United States saw a massive expansion of railroads in western states, which was accompanied by rampant speculation in western land and railroad securities. The panic was caused principally by a bust in western land speculation and the prices of speculative railroad securities, which devastated the banking system. August witnessed the demise of a major bank, the Ohio Life and Trust Company, which had a loan portfolio particularly vulnerable to the decline in western land values and railroad securities prices. In September and October, the securities market declined significantly, which increased uncertainty in the banking system and led some New York state banks to demand redemptions from New York City banks. Banks in cities such as Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Chicago began to suspend convertibility (in other words, banks refused to permit note redemptions or withdrawals) in late September. Faced with increased demand for redemption of notes and heightened uncertainty about the solvency of some major securities dealers, New York City banks responded by calling loans, forcing many securities dealers to liquidate their assets at extremely low prices and pushing many into bankruptcy.

Depositors and other banks around the country began to question the solvency of the New York City banks that provided loans to the dealers and brokers. As a result, several New York City banks experienced runs, and banks in New York City suspended convertibility on October 13. Despite widespread suspension, few banks failed during the panic. The panic ended quickly as New York City banks resumed redemption of notes on December 11. Nevertheless, the panic led to a severe recession that lasted for a year.

Image of the Run on the Seamen's Savings Bank during the Panic

March 20, 1858

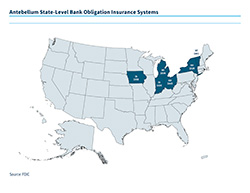

Iowa becomes the sixth state to provide insurance for bank creditors. The state passed a law creating a State Bank of Iowa, similar to banks in Indiana and Ohio, which was made up of independent branch banks. Although a free banking law was passed at the same time, only the branch banks were eligible for insurance and only the circulating notes of participating banks were covered. During the period the insurance system existed, no participating bank failed. By 1865, the system ceased operating when most of the branch banks converted to national banks.

https://www.fdic.gov/about/financial-reports/reports/archives/fdic-ar-1953.pdf

Map of the six bank obligation insurance systems put in place before the Civil War

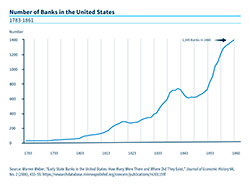

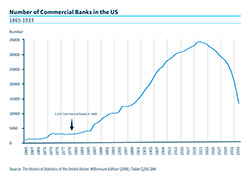

There are 1,345 banks operating in the United States.

Chart of the number of banks operating in the United States in 1860

February 25, 1863

President Abraham Lincoln signs the National Currency Act of 1863 into law. (Upon its amendment by a new law in 1864, it would become known as the National Bank Act.) The law was passed largely due to the urgent need to provide financing for the U.S. government during the Civil War. The national banks created by the statute were required to buy U.S. Treasury bonds to back the bank notes they would issue, providing the Treasury with funding for the war. Another reason for the law was the perceived need to remedy certain defects in the U.S. banking system by creating a uniform currency backed by U.S. government bonds. Up to this point, many bank notes issued by state banks circulated, but ascertaining their values and legitimacy could be difficult (counterfeiting was a significant problem, and the farther a transaction was from the issuing bank, the less information that might be available about the bank).

The law creates the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), which is to organize and administer a system of nationally chartered banks and a uniform currency. The law allows for groups of no fewer than five people to form a bank, with capital of no less than $50,000. In large cities, the capital requirement was no less than $100,000.

Banks are required to report quarterly to the OCC on the bank's condition. The Act also requires each bank to hold "lawful money of the United States" (reserves) equal to at least 25 percent of the amount of its outstanding notes. Whenever a bank falls below this threshold, it is prohibited from making new loans. National banks deposit U.S. government bonds with the Treasury and receive banknotes from the Comptroller equal to 90 percent of the value of the bonds. The Treasury can sell the bonds deposited by the bank to pay off the bank's noteholders if a bank fails to redeem its notes.

The following year, the National Bank Act of 1864 amends the National Currency Act. National banks are now required to hold reserves in a three-tiered system. New York City is designated a central reserve city, with a 25 percent reserve requirement. Regional financial centers like Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago are identified as reserve city banks that also have a 25 percent reserve requirement, but half of their reserves can be deposited in central reserve city banks. Country banks have a reserve requirement of 15 percent, and 60 percent of those reserves can be deposits in either central reserve or reserve city banks. Capital requirements vary based on the population of the city where the bank is located.

Bruce Champ, , “The National Banking System: A Brief History,” (Working Paper 07-23, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, December 2007), https://www.clevelandfed.org/en/newsroom-and-events/publications/working-papers/working-papers-archives/2007-working-papers/wp-0723-the-national-banking-system-a-brief-history.aspx .

March 1865

Congress passes a 10 percent tax on state bank notes. The National Bank Act had provided for both new national bank charters and the conversion of state banks into national banks. Relatively few state banks initially convert to national charters because they were not enamored with the law’s capital requirements, more stringent federal oversight, and restrictions on activities permitted under state laws. Congress imposes the tax to force state banks to convert to national charters. The tax led many state banks to convert to national charters.

https://www.occ.gov/about/who-we-are/history/1863-1865/index-occ-history-1863-1865.html

September-October 1873

Panic of 1873

From 1866 to 1873, the nation experienced rapid and speculative growth in railroad construction. Both U.S. banks and European investors actively financed American railroads. However, many railroad companies began having difficulties. The industry's financial predicament was partly due to a decline in demand for railroad bonds by European investors following the May 1873 Vienna stock market crash that led European investors to sell their U.S. holdings. Railroad firms found it difficult to finance their operations and pay off existing debt. Many failed and defaulted on their bank loans, affecting banks that had provided funds to the industry.

One prestigious banking firm, Jay Cooke and Co., was heavily invested in railroad companies and overextended itself. The firm declared bankruptcy in September 1873. This failure triggered immediate panic in the stock market, and many private banks in New York City experienced runs and failed. In response, the New York Clearing House (NYCH) authorized the pooling of reserves among its member banks in September, allowing the NYCH to redistribute reserves from banks with surplus reserves to banks with a shortage in order to meet the demand for cash.

The banking disturbances spread to other cities, including Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., as well as cities in the South and Midwest. Although the banking panic subsided by mid-October, the subsequent economic contraction was severe. Many railroad firms failed and railroad investment collapsed. Loans and deposits in New York national banks contracted substantially. Machinery production fell significantly in 1874 and unemployment increased.

Image of the Panic of 1873

There are 3,345 commercial banks operating in the United States.

Chart of the number of commercial banks operating in the United States in 1880

Panic of 1884

This panic and its attendant banking difficulties were less severe than other national banking-era panics. The rapid and effective response of the New York Clearing House (NYCH) prevented a full-scale banking panic; instead, only a few banks closed due to bank-specific reasons, and there was no general loss of depositor confidence.

The panic was mostly confined to New York City and began with the failures of the Marine National Bank and the private bank Grant and Ward in May 1884. Both failed due to poor management and losses in speculative investments. Later in May, there was a run on another bank, Metropolitan National, because depositors worried that the bank was involved in fraudulent speculation in railroad securities. The bank's closure led to panic on the stock market and instability in the New York money market.

Six brokerage firms failed due to their connection with Metropolitan National. The bank also had close financial links to banks in the interior and to members of the NYCH. Two-thirds of its deposits were interbank deposits from other banks. To prevent Metropolitan National's closure from affecting other banks and eroding depositor confidence elsewhere, the NYCH quickly authorized the issue of loan certificates and provided assistance directly to the bank so it could make payments to other banks. However, unlike other panics during the national banking era, the NYCH did not suspend convertibility. There were few bank closings in the rest of the country.

Image of the Panic of 1884

The first known proposal for a plan resembling national deposit insurance is introduced in the U.S. Congress; over the next five decades, more than 150 proposals will be introduced without success.

For information on these proposals, see FDIC Annual Report, 1950, 63ff, https://www.fdic.gov/about/financial-reports/reports/archives/fdic-ar-1950.pdf .

Panic of 1893

The severe Panic of 1893 differed from other panics of the national banking era in that it originated in the country's interior and spread to New York City rather than vice versa.

Two factors contributed to the panic. First, growing concerns about the government's ability to sustain the gold standard increased both foreign and domestic demand for gold, draining the U.S. Treasury's gold reserves, causing a decrease in the money supply, and contributing to stock market dislocation in early 1893. Second, the U.S. economy contracted and business failures increased, particularly in the railroad industry. The failure of railroads and other firms led to stock market declines in March and April and a stock market collapse in May. Concerns about worsening economic conditions and the associated uncertainty in the stock market could have sparked a loss of confidence in the banking system and triggered the panic.

By June there were widespread runs on banks, leading to many bank suspensions (a bank suspension is defined as a bank that is closed to the public, either temporarily or permanently, by supervisory authorities or by the bank's board of directors on account of financial difficulties) in cities such as Chicago, Omaha, Milwaukee, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Spokane, but with little banking disturbance in New York City. However, the New York Clearinghouse authorized the use of clearinghouse certificates due to the increased flow of reserves from banks in New York City to banks in the interior. In July, banking disturbances intensified with citywide panics in Kansas City, Denver, Louisville, Milwaukee, and Portland. Since bank suspensions were more severe where greater numbers of nonfinancial firm failures occurred, real economic shocks could have caused the panic. As interior banks continued to face runs, they increasingly withdrew reserves from banks in New York City, decreasing New York City bank reserves. The New York banks partially restricted cash payments to interior banks as a response, resulting in a shortage of cash for those banks.

The banking panic ended in September. A total of 503 banks suspended payments during the panic. Suspensions were heavily concentrated in the West and Northwest. The economic downturn associated with the panic was severe. Industrial production fell 15.3 percent between 1892 and 1894, and unemployment rose to more than 11 percent between 1893 and 1898.

Image of the Panic of 1893